An apology, dissolution, and a side of tear gas

A deadly, youth-led protest over power and water shortages in Madagascar has prompted a capital city curfew and a government apology.

Authorities in Madagascar have imposed a dusk-to-dawn curfew in the capital Antananarivo after youth-led protests over chronic power cuts and water shortages spiralled into deadly unrest. Police fired tear gas at thousands of demonstrators who defied a ban on gatherings, while looters ransacked shops, torched a mall and vandalised lawmakers’ homes. General Angelo Ravelonarivo, head of a joint police-military security body, said the curfew would run from 1900 to 0500 hours, “until public order is restored.” The United Nations reported that at least 22 people were killed and more than 100 were injured over three days of protests, the biggest in years. The government dismissed the UN figures as “rumours.” In a televised address, President Andry Rajoelina apologised for government failures, announced the dissolution of his cabinet, and promised dialogue with young people and relief for businesses hit by looting. “I heard the call, I felt the suffering,” he said. Rajoelina, re-elected in 2023, faces mounting criticism for failing to improve living conditions. The protests, partly inspired by recent “Gen Z” movements in Kenya and Nepal, represent the most serious challenge to his leadership since his disputed re-election.

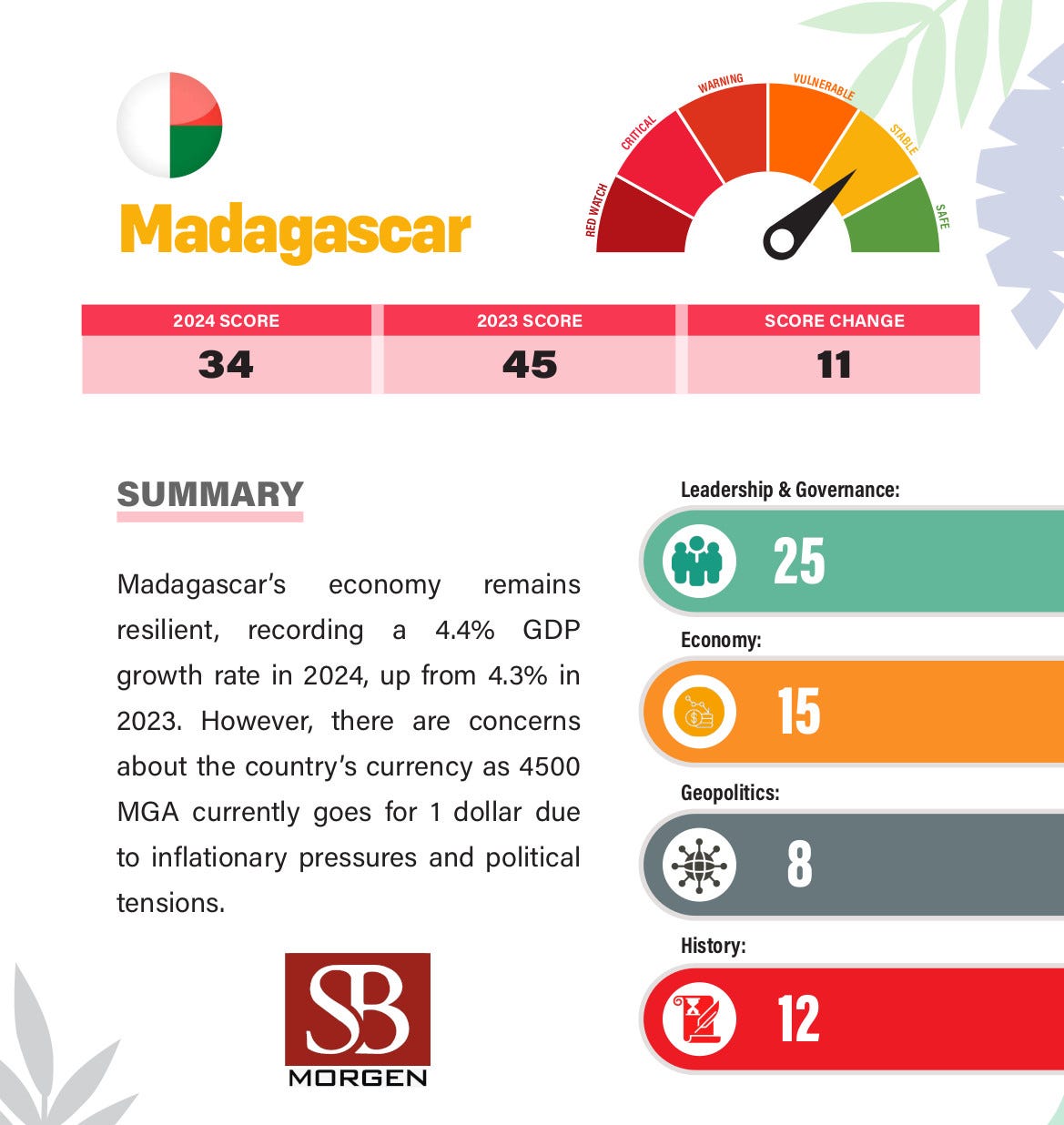

The unrest in Madagascar is a stark reminder of how unmet socio-economic needs, weak governance, and authoritarian reflexes converge to destabilise fragile democracies. Chronic electricity blackouts and water shortages, rooted in mismanagement at state utility Jirama, were the immediate spark. But the deeper drivers are long-standing: unfulfilled promises of better living standards since President Andry Rajoelina’s disputed 2023 re-election, accusations of corruption, and widespread frustration with basic service delivery. For households and businesses, these failures translate into declining quality of life and lost productivity, while at the macro level, they erode investment confidence and blunt growth prospects.

The demonstrations, inspired partly by Kenya’s “Gen Z” tax protests and youth movements in Nepal, underscore how digitally connected populations are increasingly willing to mobilise against entrenched political elites. The parallels with Rajoelina’s own rise in 2009 are striking: youth-led protests over governance failures, looting and arson in Antananarivo, and a cabinet reshuffle deployed as a pressure valve. Yet, as seen in Kenya in 2024 and Sudan in 2018, sacking ministers rarely addresses structural grievances. Cabinet dissolutions can buy time, but, absent credible reform, they are quickly dismissed as cosmetic.

The human cost is mounting. The UN reports at least 22 deaths and over 100 injuries, though the government contests the figures. What is indisputable is the violent repression, with security forces deploying tear gas and live ammunition. This reflects a broader regional pattern where governments treat protests not as constitutionally protected civic expression but as threats to regime survival. The result is an erosion of rights, deepening distrust, and the radicalisation of already disaffected youth.

Looking ahead, Madagascar’s growth outlook—projected at 4.7 percent annually through 2027—faces headwinds from climate shocks, volatile commodity revenues, and rising debt dependence. Unless coupled with real improvements in utilities, governance reforms, and inclusive dialogue with the country’s youthful population, Rajoelina’s pledges risk ringing hollow. For policymakers, the lesson is clear: basic service provision is not just an economic necessity but a foundation of political legitimacy. Heavy-handed repression may silence protests temporarily, but without structural reform, it only accelerates the cycle of instability.