Bridging waters

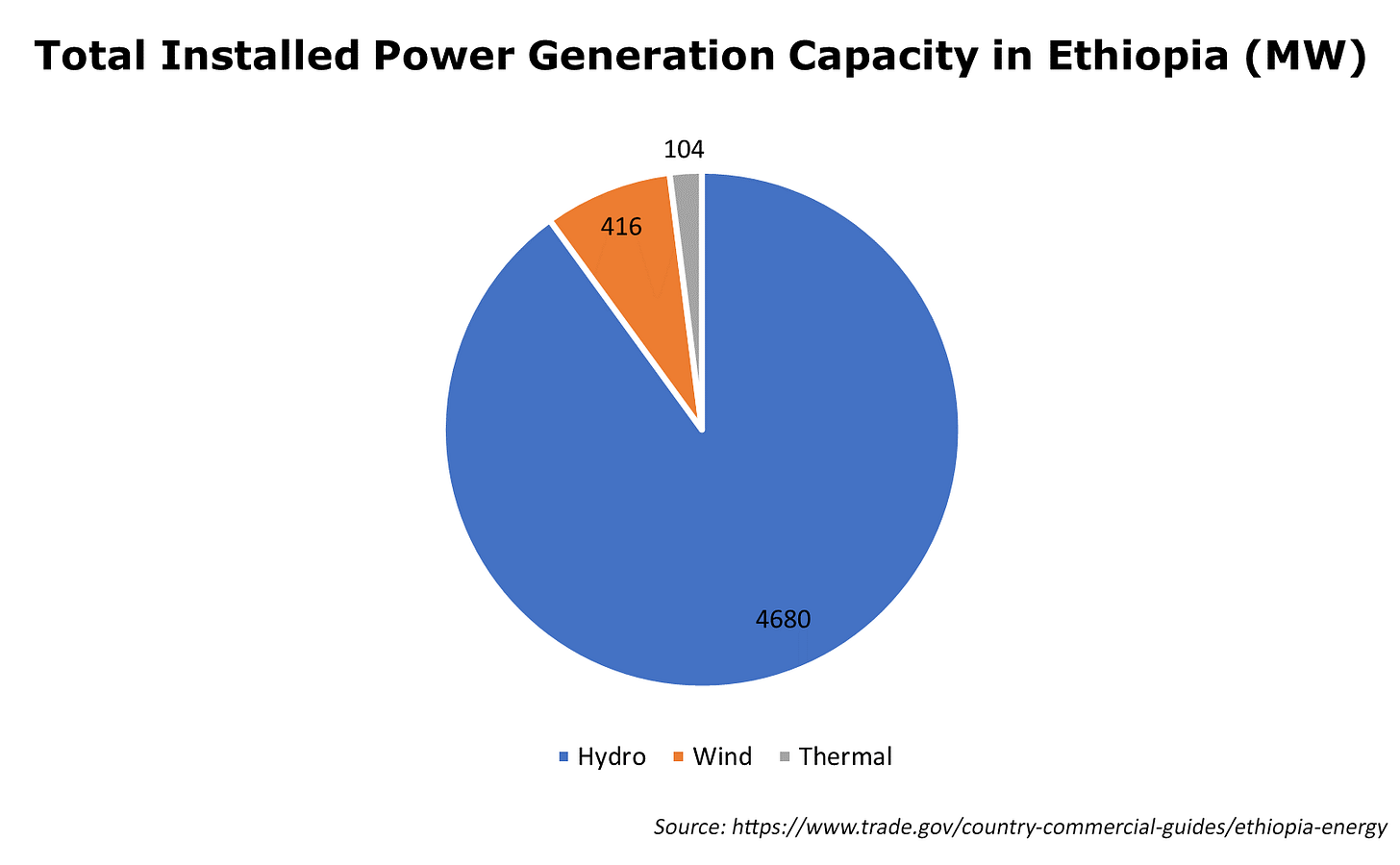

Ethiopia completes GERD, Africa's largest hydro dam, despite Nile tensions. The $4bn project aims to generate 6,000MW and boost regional energy exports.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has announced the completion of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD), Africa’s largest hydroelectric project. Initiated in 2011 with a $4 billion budget. The dam spans 1,800 metres and stands 175 metres high, with a 74-billion-cubic-metre reservoir. Despite regional tensions—particularly with Egypt and Sudan over Nile water rights—Abiy reaffirmed Ethiopia’s intent for mutual development without harming downstream nations. The GERD, which began generating power in 2022, is expected to produce over 6,000 megawatts of electricity, aiming to reduce poverty and make Ethiopia a key energy exporter. Its official inauguration is scheduled for September.

The completion of GERD marks a pivotal moment for Ethiopia's energy ambitions and the geopolitical landscape of the Nile Basin. After over a decade of complex engineering, geopolitical wrangling, and intermittent tensions, Addis Ababa has delivered Africa's largest hydroelectric project, symbolically affirming its determination to redefine the balance of power in the region.

At its core, GERD is a nation-building project. Ethiopia has long grappled with chronic energy shortages and underdevelopment, particularly in its rural areas. With a projected output exceeding 6,000 megawatts of electricity, GERD represents the most transformative infrastructural intervention in the country's modern history. It promises to expand electricity access to millions, support industrialisation, and establish Ethiopia as a significant power exporter to the Horn of Africa and beyond. For Addis Ababa, electricity is thus both a domestic stabiliser and a strategic foreign policy tool.

Despite this achievement, the dam's completion does not resolve the deeper geopolitical fault lines it has exposed. Egypt's description of GERD as an "existential threat" is not mere rhetoric; it reflects the profound hydrological and psychological centrality of the Nile to Egyptian national identity and survival. Cairo's longstanding position—that any unilateral upstream action threatens its historical water share—is rooted in colonial-era treaties that Ethiopia has never recognised. Sudan, while more ambivalent, remains wary of potential disruptions to its own water infrastructure.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed's discourse of shared progress and regional solidarity offers a conciliatory narrative, yet it sidesteps the fundamental issue: how will riparian tensions be sustainably managed in the absence of a binding water-sharing agreement? African Union mediation efforts have so far lacked enforceable mechanisms, while external actors—from the Arab League to the United States—have appeared inconsistent or been perceived as partial.

In geopolitical terms, GERD is more than just a dam; it embodies a broader trend of African states asserting sovereign developmental priorities over inherited geopolitical constraints. For landlocked Ethiopia, historically marginalised in regional trade and security structures, GERD symbolises a strategic ascent, practically and metaphorically anchoring its ambitions.

Looking ahead, Abiy will likely promote the September inauguration as a capstone to his vision of a "New Ethiopia," even as his domestic legitimacy faces strain from protracted conflicts in Tigray, Amhara, and Oromia. For Egypt and Sudan, the challenge now lies in recalibrating their Nile diplomacy in a post-GERD reality, where upstream hydro-sovereignty is no longer aspirational but operational.

Egypt's concerns are exacerbated by its fixed annual allocation of 55.5 billion cubic metres from the Nile, which falls short of meeting rising demands driven by population growth, agriculture, and industry. This pressure is compounded by climate change, intensifying evaporation and increasing water consumption. With a population now exceeding 114 million and hosting millions of refugees, Egypt's static water quota increasingly struggles to meet basic needs. GERD, towering over 140 metres with a reservoir comparable in size to Greater London, is seen by Cairo as further exacerbating its water scarcity, threatening its agricultural ambitions, and potentially forcing greater reliance on food imports. In response, Egypt has invested heavily in wastewater treatment and desalination plants, with several agricultural initiatives now dependent entirely on treated water—a strategic adaptation to these emerging challenges.

Relations between Cairo and Addis Ababa reached a peak of tension in 2020, when Egypt escalated its opposition by seeking support from the United States and Sudan. At the time, the Trump administration expressed strong support for Egypt, which was influenced by sympathy for the Tigray region during Ethiopia’s internal conflict (leading to sanctions against the Abiy government) and a desire for Egypt’s support in the Abraham Accords. In September 2020, Washington announced aid cuts after Ethiopia began filling the dam’s reservoir in July, with Trump controversially suggesting Egypt might "blow up" the dam. Egypt responded by conducting live-fire military drills jointly with Sudan, signalling its willingness to use force.

While the Biden administration adopted a more measured tone, advocating for a negotiated settlement (a position largely maintained by the new Trump administration), Egypt’s foreign minister recently declared the failure of diplomatic avenues, citing Ethiopia’s perceived intransigence. Labelling the dam a "red line" and an "existential threat," Cairo has indicated that military options remain on the table.

Between 2014 and 2022, Egypt sought to consolidate its influence by cultivating strategic ties with South Sudan and Uganda. However, efforts to counter Ethiopia’s sway in South Sudan faced strong resistance, particularly from the Nuer, who maintained longstanding ties with Ethiopia. Cairo may now explore exploiting Ethiopia’s internal instability, notably the Fano rebellion in Amhara, to weaken Addis Ababa’s stance on GERD. Covert support for Fano militants—whether through regional proxies or intelligence sharing—could exacerbate internal divisions and divert Ethiopian resources from dam operations to domestic conflict. Additionally, Egypt might seek to amplify anti-Abiy sentiment via support for opposition media and diaspora networks, undermining Ethiopia’s regional standing. Strengthening alliances with Eritrea and Somalia could further isolate Ethiopia diplomatically, increasing pressure for concessions. Such actions, however, risk heightening regional tensions and attracting international condemnation.

More recently, a surprising rapprochement between Somalia and Eritrea has emerged, driven by shifting regional dynamics. Tensions between Mogadishu and Addis Ababa over Somaliland’s autonomy have brought Somalia closer to Egypt, as both seek to contain Ethiopia’s expanding influence. Yet, without explicit or tacit support from Washington, a military response from Egypt remains improbable. Trump’s aversion to foreign conflicts makes regional instability unattractive, especially as his advisers increasingly push for American recognition of Somaliland as a counter to Chinese influence in the Horn of Africa.

If managed prudently, GERD could catalyse regional energy integration, with Ethiopia supplying power to its neighbours and fostering mutual interdependence. However, the realisation of these benefits hinges on the establishment of a credible, transparent water management regime that genuinely addresses downstream concerns.

Ultimately, GERD’s significance may lie as much in the precedent it sets as in the power it generates: African development need not remain hostage to downstream vetoes. Moving forward will require new rules, robust trust-building mechanisms, and a genuine political commitment to cooperative river basin governance. Without a comprehensive agreement, the door remains open to future disputes, particularly during periods of hydrological stress. Though a technical triumph for Ethiopia, the dam’s completion marks not the end of the Nile dispute, but the beginning of a more complex phase in regional relations.