Budget predicts slightly less money magic

Nigeria has approved its three-year budget framework, projecting lower revenue and allocations amid conservative economic assumptions ahead of the 2027 elections.

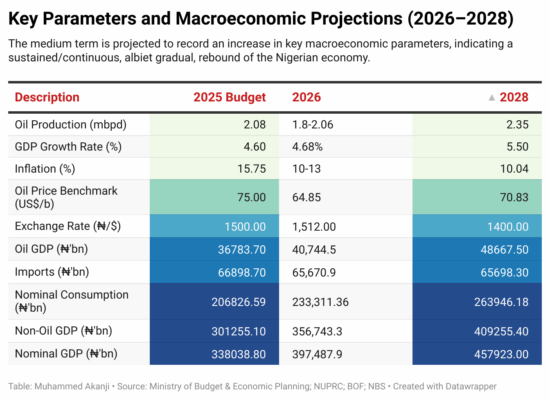

Nigeria’s Federal Executive Council has approved Nigeria’s 2026–2028 Medium-Term Expenditure Framework, outlining fiscal targets and spending priorities for the next three years. Budget and Economic Planning Minister Atiku Bagudu said federal revenue for 2026 is projected at ₦34.33 trillion, including ₦4.98 trillion from government-owned enterprises, about ₦6.55 trillion lower than the 2025 estimate. Statutory transfers are expected to hit ₦3 trillion, while federal allocations will fall by about 16% to ₦9.4 trillion. Key assumptions approved include an oil production benchmark of 1.8 million barrels per day (mbpd) for budgeting (against a target of 2.6mbpd), an oil price of $64 per barrel, and an exchange rate of ₦1,512/$, reflecting expected fiscal pressures ahead of the 2027 elections. Finance Minister Wale Edun also announced the approval of a $100m AfDB youth investment facility and an Islamic Development Bank agricultural programme in Yobe, as President Tinubu urged capital spending that drives growth and jobs.

Nigeria’s newly approved 2026–2028 Medium-Term Expenditure Framework offers a window into the federal government’s fiscal priorities ahead of a politically consequential period. With projected revenue for 2026 placed at ₦34.33 trillion, a notable ₦6.55 trillion drop from the 2025 estimate, the numbers already hint at tightening room. Statutory transfers are expected to rise to ₦3 trillion, while federal allocations are set to fall by about 16% to ₦9.4 trillion, signalling an environment where expenditure pressures may outpace available resources.

The assumptions anchoring the framework — 1.8mbpd oil production, $64 per barrel oil price, and an exchange rate of ₦1,512/$ — reflect a government acknowledging fiscal fragility even as it tries to project stability. That fragility will define the political economics of the next three years. But the significance of 2026 extends far beyond numbers. It is the eve of the 2027 elections, a period when Nigeria’s fiscal books have historically been shaped not only by economic factors but also by political incentives. Political spending tends to arrive in waves — subsidies, capital projects, transfers and employment schemes — all designed to secure electoral goodwill. Such expenditures, while stimulatory on the surface, have a predictable effect: they loosen fiscal discipline.

If unrestrained, it could inject liquidity into an economy still testing its recovery and sensitive to shocks, raising the risk of money-supply-driven inflation. The government’s decision to project lower revenues as a cycle of higher political pressure approaches is therefore as much a warning as a plan. The approvals of a $100 million AfDB youth investment facility and an Islamic Development Bank agricultural programme in Yobe are welcome for growth, but they come alongside a broader risk: that election-cycle expenditure may outpace revenue growth, widening deficits already under strain. Nigeria is entering 2026 with a policy challenge that demands discipline: how to fund growth without triggering inflation and how to spend politically without destabilising the economy. Tinubu’s call for capital spending that drives jobs and output is sound macroeconomics. Whether it survives the logic of election season will be the real test.