Cedi finally wins an award

In 2025, Ghana's economy rebounded strongly as its currency, the cedi, appreciated significantly and national foreign reserves hit a record high.

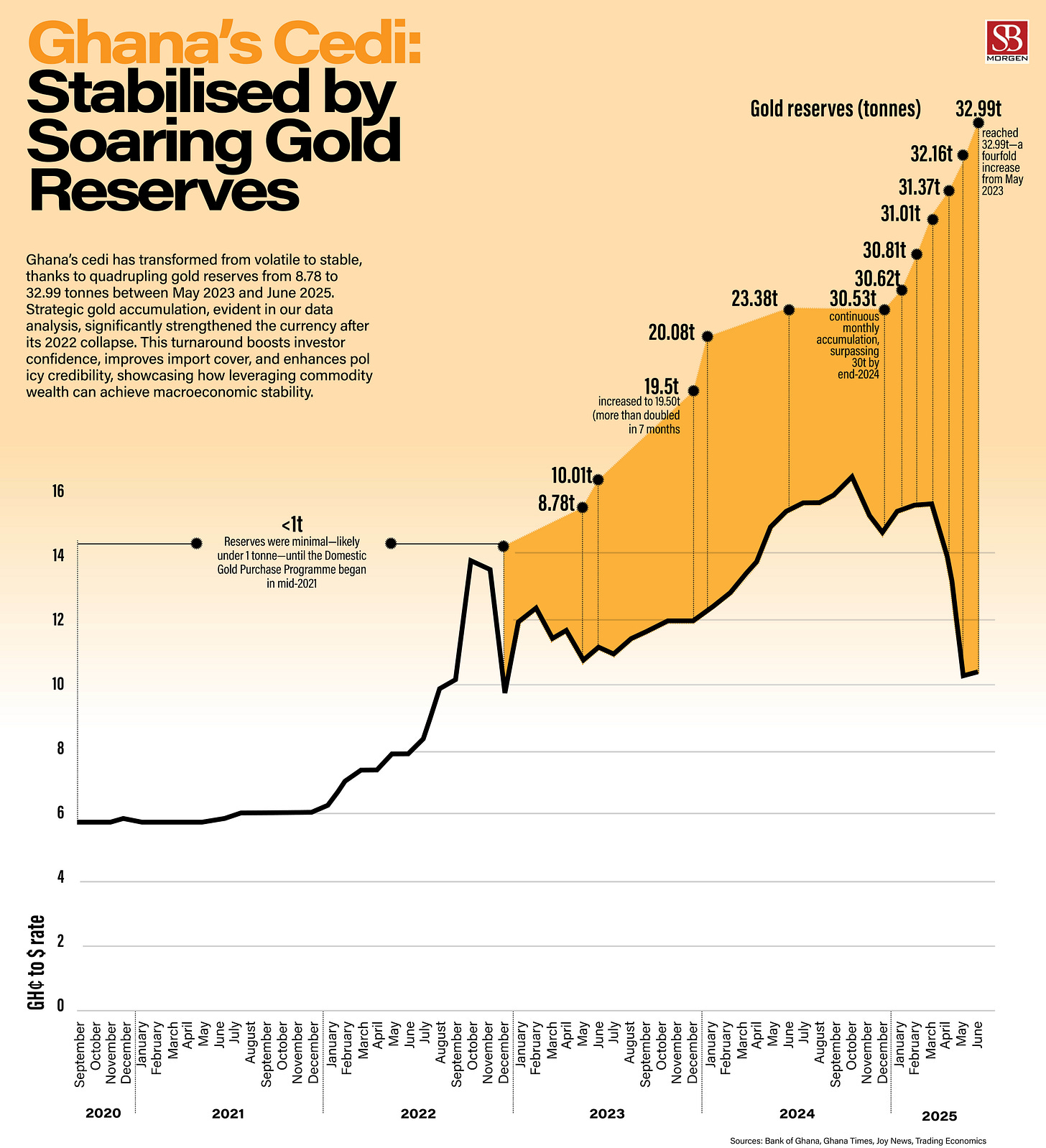

Ghana’s economic recovery gathered pace in 2025, driven by a historic rally in the cedi, a sharp rise in foreign reserves, and a formal move toward exiting the International Monetary Fund (IMF) programme. The cedi recorded its first annual gain against the US dollar in nearly three decades, appreciating by 41%. Bloomberg data show it was the second-best performer among 144 currencies tracked globally, marking its strongest showing since records began in 1994. The gains were supported by higher global gold prices, a weaker dollar, and improving investor confidence. Ghana’s external buffers also strengthened. International reserves climbed to a record $13.8 billion by the end of 2025, even after a $709 million Eurobond repayment in December. Without the early debt payment, reserves could have exceeded $14 billion. Analysts credit stronger fiscal revenues, the Bank of Ghana’s reserve-building.

Ghana’s third-quarter economic growth of 5.5% and the cedi’s historic 41% appreciation present a narrative of a “Golden Recovery,” yet this resurgence is increasingly shadowed by structural contradictions and deep commodity dependence. The currency’s strength has been driven largely by elevated global gold prices and deliberate policy choices, notably the Gold-for-Reserves strategy and the GoldBod initiative, which have channelled gold earnings directly into foreign exchange buffers. As Africa’s largest gold producer and a major cocoa exporter, Ghana has benefited disproportionately from the current commodity cycle, allowing the central bank to rebuild reserves to roughly six months of import cover and intervene aggressively in FX markets.

These interventions have been substantial. The Bank of Ghana is estimated to have injected close to $10 billion to stabilise the cedi, anchoring expectations and reinforcing the perception of macroeconomic control. The stronger currency has fed through to headline indicators. Inflation fell sharply, ending 2025 in the mid-single digits, while lower import duties and declining fuel prices eased pressure on households and firms. Improved price dynamics gave the central bank room to cut policy rates by a cumulative 1,000 basis points, loosening credit conditions and supporting growth momentum as Ghana entered 2026.

However, the durability of this recovery is far from assured. The cedi’s strongest performance in three decades has coincided with a sharp rise in public debt, which reached 684.6 billion cedis by September. This “debt-currency paradox” exposes a core vulnerability. A significant share of Ghana’s liabilities remains foreign-currency denominated, meaning that even brief episodes of exchange-rate weakness could rapidly inflate the debt stock and erase fiscal gains. In this context, currency stability is not just a macroeconomic achievement but a fragile prerequisite for debt sustainability.

The government’s intention to exit the IMF programme in 2026 further sharpens the stakes. Supporters frame the move as a transition from a bailout economy to a sovereign one, underpinned by fiscal discipline and improved external buffers. Critics, however, see it as a calculated gamble on the persistence of high gold prices rather than a signal of deep structural transformation. The IMF itself continues to classify Ghana as being at high risk of debt distress, warning that a sharp correction in gold prices could abruptly reverse recent gains despite efforts to reduce the debt-to-GDP ratio below 50 percent.

Policy contradictions are also becoming more pronounced. The ban on mining in forest reserves reflects a genuine commitment to environmental protection, but it sits uneasily alongside the state’s growing reliance on gold production to stabilise reserves and support the currency. This tension creates a strategic bottleneck. Limiting mining output while depending on gold inflows narrows policy space and increases exposure to price volatility, especially in the absence of alternative export drivers.

For ordinary Ghanaians, the recovery remains uneven. While inflation has fallen, recent increases in utility tariffs highlight a persistent disconnect between macroeconomic indicators and lived experience. Currency strength on paper does not automatically translate into lower household costs, and the social sustainability of the recovery will depend on whether growth gains are felt more broadly.

Looking ahead, Ghana’s challenge is not managing a commodity upswing, but surviving its eventual reversal. Elevated gold prices have bought time, rebuilt confidence, and restored a degree of macroeconomic stability. Whether this moment becomes a durable turning point will depend on how effectively Accra uses the current window to deepen diversification, entrench fiscal discipline beyond IMF oversight, and reduce its exposure to volatile commodity cycles. Without that shift, the “Golden Recovery” risks being remembered less as a structural breakthrough and more as another pause in Ghana’s long-running adjustment story.