China tightens purse strings across Africa

Chinese loans to Africa halved in 2024, shifting towards smaller, strategic investments as Beijing adopts a more cautious economic approach.

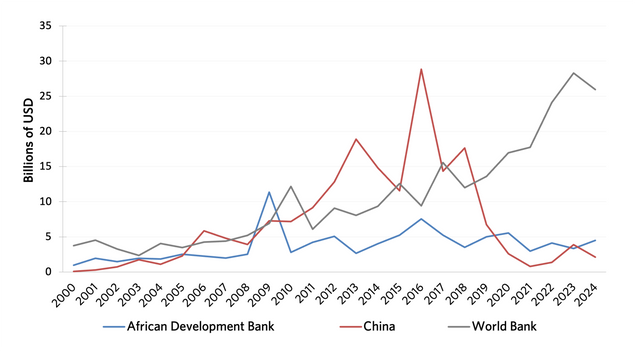

Chinese lending to Africa nearly halved in 2024, dropping to $2.1 billion, the first annual decline since the COVID-19 pandemic, according to data from Boston University. This represents a sharp decline from the $28.8 billion peak in 2016 and reflects China’s shift from large-scale infrastructure megaprojects toward smaller, commercially viable, and strategically targeted investments. The Boston University report notes that Beijing has increasingly favoured yuan-denominated loans, financing through African banks, SME on-lending, and foreign direct investment over traditional dollar-denominated development loans. In 2024, only six projects were funded across the continent, with Angola receiving $1.45 billion for power grid and road upgrades. Researchers argue that the trend reflects a more cautious, market-oriented approach, reducing debt risk while supporting sustainable growth. Chinese lending via regional banks and commercially driven projects is expected to continue in 2025, signalling a new, selective phase of engagement in Africa.

China’s dramatic reduction in lending to African countries signifies a strategic pivot rather than an admission of failure. The transition from multi-billion-dollar “megaprojects” to smaller, commercially viable investments, often termed the “Small yet Beautiful” model, reflects a move toward financial sustainability. Lending to the continent fell to just $2.1 billion in 2024, a drop of 46 percent from the previous year, and a fraction of the $29 billion peak in 2016.

Beijing is effectively de-risking its portfolio. It now favours yuan-denominated loans and utilises regional banks for on-lending. This promotes the internationalisation of its currency while ensuring investments are deeply embedded in critical value chains. Angola, for instance, received nearly 70 percent of all Chinese loans in 2024, primarily for power and road infrastructure. This “selective engagement” secures China’s long-term access to raw materials essential for its industrial dominance.

For African countries, this shift marks a transition from passive recipients of capital to strategic arbiters in a multicentric world. As China becomes more disciplined, African nations are leveraging their “energy transition minerals” to demand better terms. Zimbabwe, for example, has banned the export of raw lithium to promote local processing, with Chinese firms already operating five lithium mines there.

This new era of resource nationalism is spreading. Nigeria is also pushing for domestic processing hubs, requiring mining licences to be tied to local refining plans. The country aims to process at least 30 percent of minerals locally. By playing major powers against one another, African states are unbundling their dependencies.

They are fostering competition in which the winning partner is not merely the one with the deepest pockets, but the one most willing to support internal industrialisation. This is critical, as the continent sends more money to China in debt repayments than it receives in new loans, resulting in a $52 billion net outflow between 2020 and 2024. The game has changed: it is no longer just about infrastructure; it is about value addition and fiscal autonomy.