Schools reopen amid relentless violence elsewhere

Deadly attacks struck multiple Nigerian states, killing rangers and farmers. Some northern schools cautiously reopened amid persistent violence, while others remained closed.

Insecurity intensified across Nigeria this week as deadly attacks continued in several states, even as schools cautiously reopened in parts of the north. In Oyo State, suspected bandits killed at least five National Park Service rangers during a night assault on an office inside Old Oyo National Park, while armed herders separately killed five farmers in a border community in Benue State. In Niger State, suspected bandits killed four people in Damala village, barely a week after earlier mass killings in the area, prompting renewed security operations. Meanwhile, schools across parts of northern Nigeria began reopening after months of closure following mass abductions, though many institutions in Niger State remained shut, underscoring persistent risks to education amid ongoing violence.

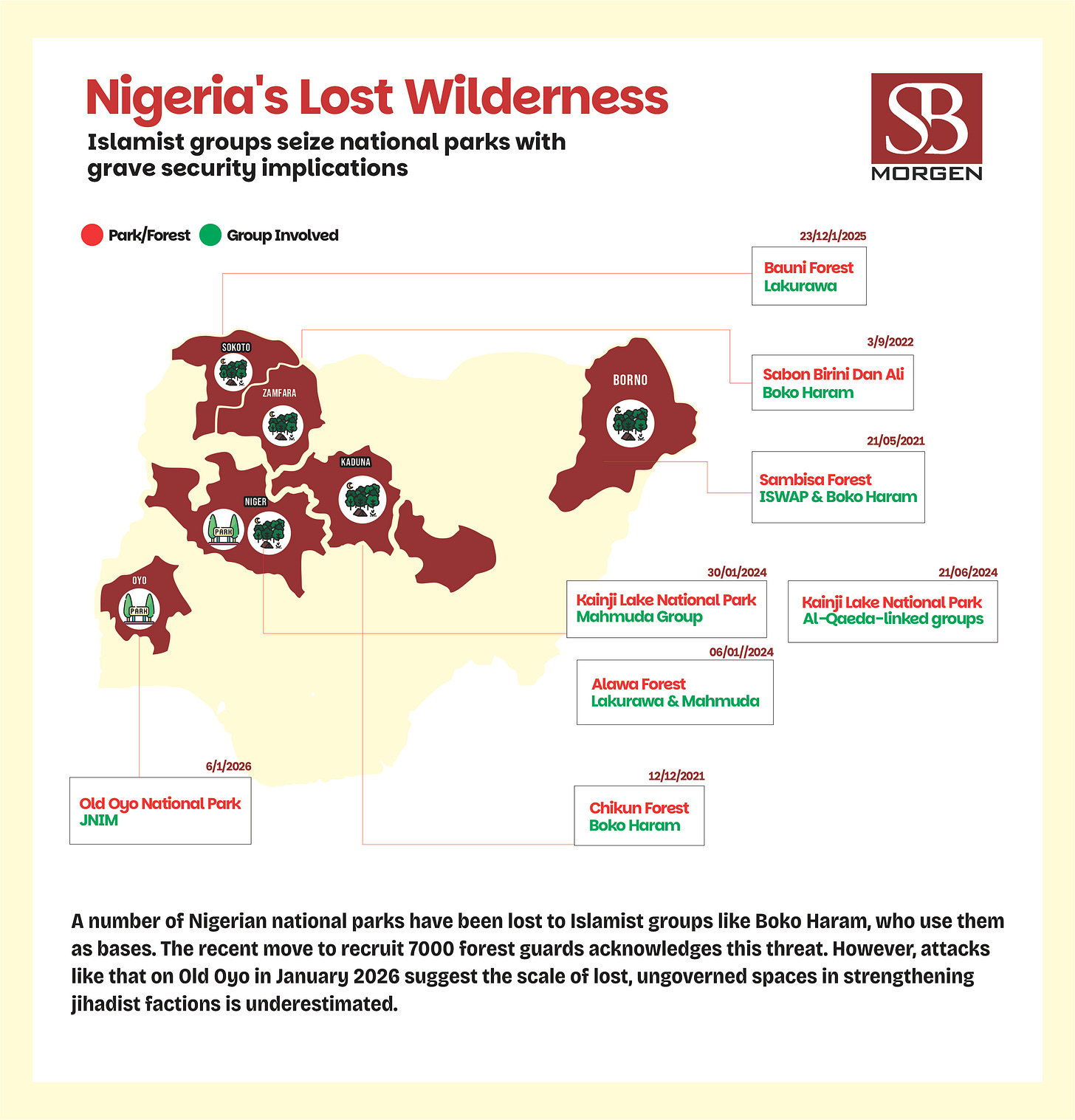

Nigeria’s security crisis continues to expose the severe limits of reactive state power. The recent killing of National Park Service rangers inside Old Oyo National Park is particularly telling. What was once viewed as a sanctuary for conservation and tourism has transformed into another theatre of organised violence, demonstrating how criminal and militant networks are expanding into spaces previously considered peripheral. This incident was far from random; rather, it reflects a dangerous convergence of banditry, Islamist militancy and illegal mining that has become central to insecurity across Nigeria’s northwestern and northcentral geopolitical zones.

In the Oyo incident, illegal miners frustrated by the arrests of their associates reportedly instigated armed groups to attack the park office in Oloka village, Orire Local Government Area. Prior to this assault, gunmen had repeatedly attempted to penetrate the park but were repelled by joint patrols of rangers and security forces. The trajectory of the attack, originating from the Kaiama and Baruten areas of Kwara State, strongly implies the involvement of Al Qaeda-aligned groups such as Mahmuda or JJNIM. These groups publicly announced their presence in Nigeria in October following the killing of a soldier in a forest community in Kwara State. Beyond cattle rustling and informal taxation, illegal mining has become a critical revenue stream sustaining these militant operations across the west of the country.

This emerging pattern in Oyo mirrors established dynamics elsewhere. In Shiroro, Niger State, informal arrangements reportedly exist between bandits loyal to Dogo Gide and Islamist factions to partition operating territories and monetise mineral resources. In parts of Zamfara and the wider North West, armed groups have even provided protection services for foreign miners, including Chinese operators. Despite estimates that Nigeria loses approximately nine billion dollars annually to this illicit trade, efforts to curb it remain fragmented. The Ministry of Solid Minerals’ plan to deploy 2,200 mining marshals has made little impact on these entrenched networks, reflecting the same weak execution that has characterised broader security interventions.

The state’s inability to secure territory extends beyond resource zones to agricultural heartlands. In Benue, the killing of farmers by armed herders highlights the unresolved nature of the conflict between farming and herding communities, where competition over land and livelihoods intersects with weak policing, ethnic tension and the proliferation of small arms. Similarly, repeated attacks within days of each other in Niger State underline the absence of credible deterrence. Security operations announced in the wake of mass killings rarely translate into sustained territorial control, merely allowing armed groups to withdraw temporarily before regrouping to strike again.

Against this volatile backdrop, the cautious reopening of schools in northern Nigeria is a fraught trade-off rather than a genuine security breakthrough. Authorities face immense pressure to resume learning after months of closures triggered by mass abductions, yet the continued shutdown of many schools in Niger State exposes how uneven and fragile these efforts remain. The resumption is partial at best, effectively asking parents, teachers and administrators to absorb security risks that the state has failed to manage. Decisions to close schools following threats are less a sign of prudence than an admission of limited control, signalling that education is treated as optional in a country with between 10 and 20 million out-of-school children, a figure accounting for up to 15 percent of the global total.

The implications for Nigeria’s human development trajectory are severe. Persistent disruption to education in the north will further depress literacy, deepen dropout rates and widen gender disparities, particularly for girls. Over time, this will entrench a two-speed country in which southern states continue to accumulate human capital while large parts of the north fall further behind. Given that the country’s demographic growth is heavily concentrated in the north, this imbalance poses a strategic risk: a rapidly expanding population without commensurate skills, productivity, or opportunities.

Ultimately, the economic costs extend well beyond lost schooling. Educational decline driven by insecurity weakens the future labour force, constrains social mobility, and reduces the long-term returns on public investment. The spread of violence across conservation zones, farming communities, mining areas and schools demonstrates that insecurity in Nigeria is no longer episodic but structural. As public trust erodes and social vulnerability deepens, immediate military responses deliver diminishing returns. Without policing led by intelligence, serious action against illegal resource economies, community-based security mechanisms and governance reforms that address root causes, Nigeria risks normalising violence as a permanent condition. This outcome would carry profound consequences for human development, economic cohesion and long-term national stability.