Security talks come with free tourism

A US delegation visited Abuja for security talks, focusing on counter-terrorism and addressing concerns over alleged religious persecution, which Nigeria disputes.

A United States congressional delegation visited Abuja on Sunday to meet Nigeria’s National Security Adviser, Nuhu Ribadu, as both countries strengthen security cooperation amid US concerns over alleged religious persecution. The delegation, which included Representatives Mario Díaz-Balart, Norma Torres, Scott Franklin, Juan Ciscomani, and Riley Moore, met alongside US Ambassador Richard Mills. Ribadu described the talks as a “fact-finding mission” focused on counter-terrorism, regional stability, and deepening the Nigeria–US strategic security partnership. The meeting follows Ribadu’s recent visit to Washington, D.C., amid a US congressional push to classify Nigeria as a “Country of Particular Concern” over claims of Christian persecution, a narrative the Nigerian government rejects as misleading. Officials emphasised that Nigeria’s security challenges affect all communities and stressed continued collaboration with international partners to combat terrorism while resisting narratives that inflame religious tensions. The visit underscores Washington’s growing engagement with Nigeria on security and counter-terrorism priorities.

For over a month, Nigeria’s relationship with the United States has been defined by America’s renewed focus on the plight of Nigerian Christians. This scrutiny culminated in the Trump Administration’s redesignation of Nigeria as a country of particular concern. While constructive engagement is undoubtedly preferable to the combative stance adopted by some government agents, the Tinubu administration’s handling of this fallout has ranged from mildly impressive to remarkably poor.

The most glaring failure has been the two-year delay in appointing ambassadors to key diplomatic missions. This vacancy created a void, leaving Abuja unable to engage Washington at senior levels, particularly on sensitive matters of religious freedom, security, and human rights. Consequently, in the absence of strong diplomatic representation, senior Nigerian security officials found themselves meeting with junior State Department officers rather than the top-tier policymakers who shape US foreign policy. The recent rush to fill these positions, which came only after the redesignation, highlights the government’s reactive approach.

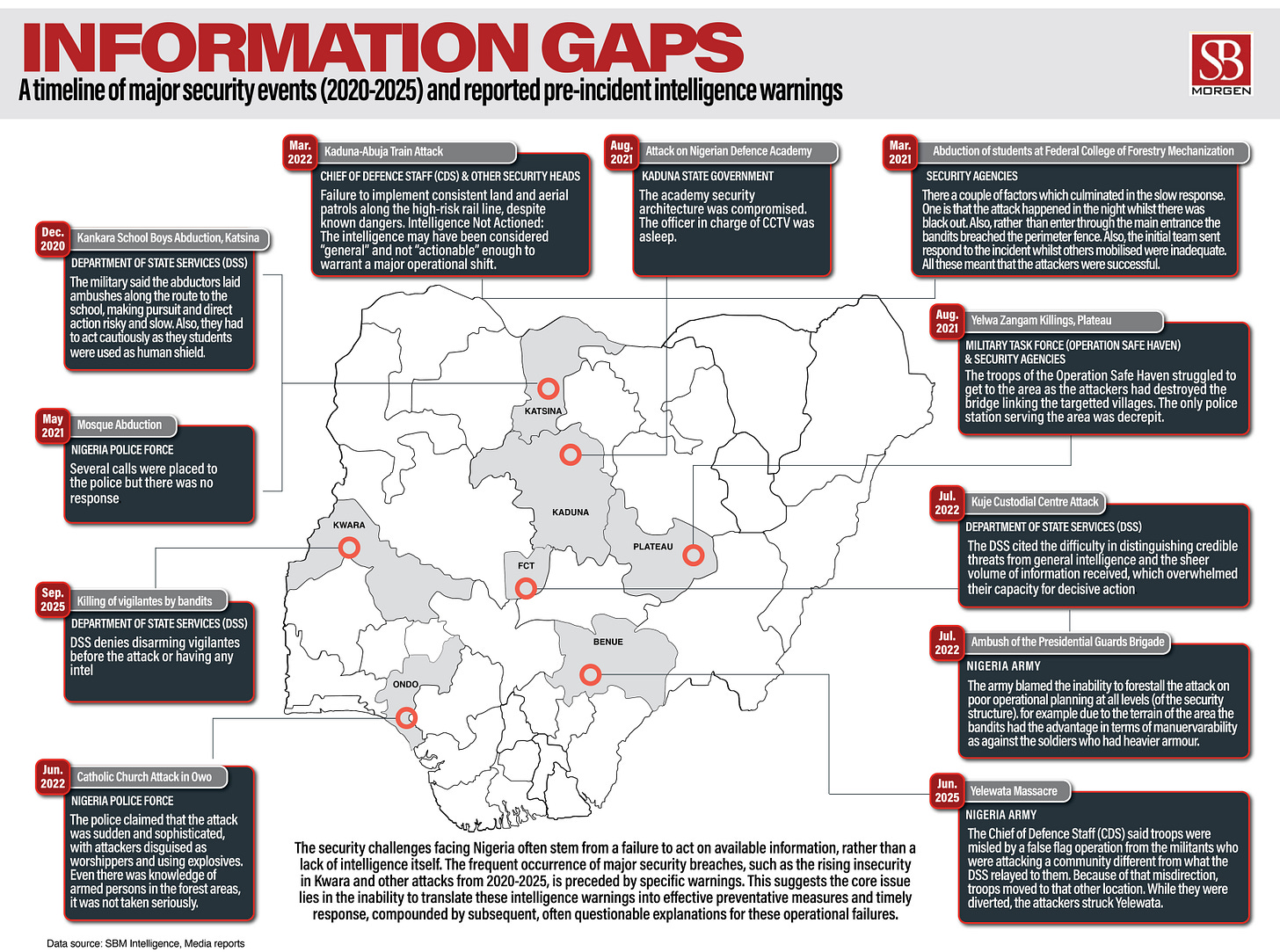

Nevertheless, it would be unfair to suggest that every aspect of Abuja’s response has been mismanaged. The administration has successfully pivoted from an unproductive narrative of denial to a more constructive appeal for collaboration. This shift appears to have opened a channel for intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance flights over terrorist enclaves in northern Nigeria. These are valuable tools for tracking insurgent movements, identifying kidnap networks, and improving battlefield awareness; however, such cooperation addresses only one part of Washington’s expectations. While diplomatic exchanges have focused on threats from Boko Haram and allied Islamist groups, these discussions alone are unlikely to satisfy American lawmakers, whose scrutiny is driven by human rights considerations and pressure from their own religious advocacy electorates.

Despite these strategic gains, a shameful reality persists: American representatives have frequently demonstrated greater concern over the wanton killings in Nigeria’s Middle Belt than representatives in Nigeria’s own upper and lower legislative houses. This is a dereliction of duty that cannot be ignored. While the Nigerian government has recently made visible attempts to appear responsive to these killings, this raises an uncomfortable question. If protecting citizens is a constitutional obligation of the state, why did it require external pressure from Washington for the administration to act with urgency?

This dependence on external scrutiny underscores a deeper governance problem in which domestic institutions fail to fulfil their responsibilities until an international spotlight compels action. Continued pressure from the US, whether welcomed or not, may ultimately act as a lifeline for Nigerians living in violence-prone regions of the Middle Belt. However, reliance on foreign advocacy underscores that Nigeria’s political class has ceded moral leadership to foreign governments. This vacuum undermines public confidence in democratic oversight and raises serious questions about Nigerian legislators' priorities.

Nigeria thus finds itself at an inflexion point. Productive engagement with the United States could yield security gains, diplomatic partnerships and a more coordinated approach to insurgent violence. Yet this engagement must be anchored in Nigeria’s own commitment to transparency, accountability and the protection of its citizens. Without reforms that demonstrate internal political will, American pressure will remain a stopgap rather than the foundation of a stable security environment. A mature relationship with Washington requires more than reactive diplomacy; it demands credible state action, consistent governance and a political class willing to take responsibility for safeguarding the lives of those they represent.