The kill zone

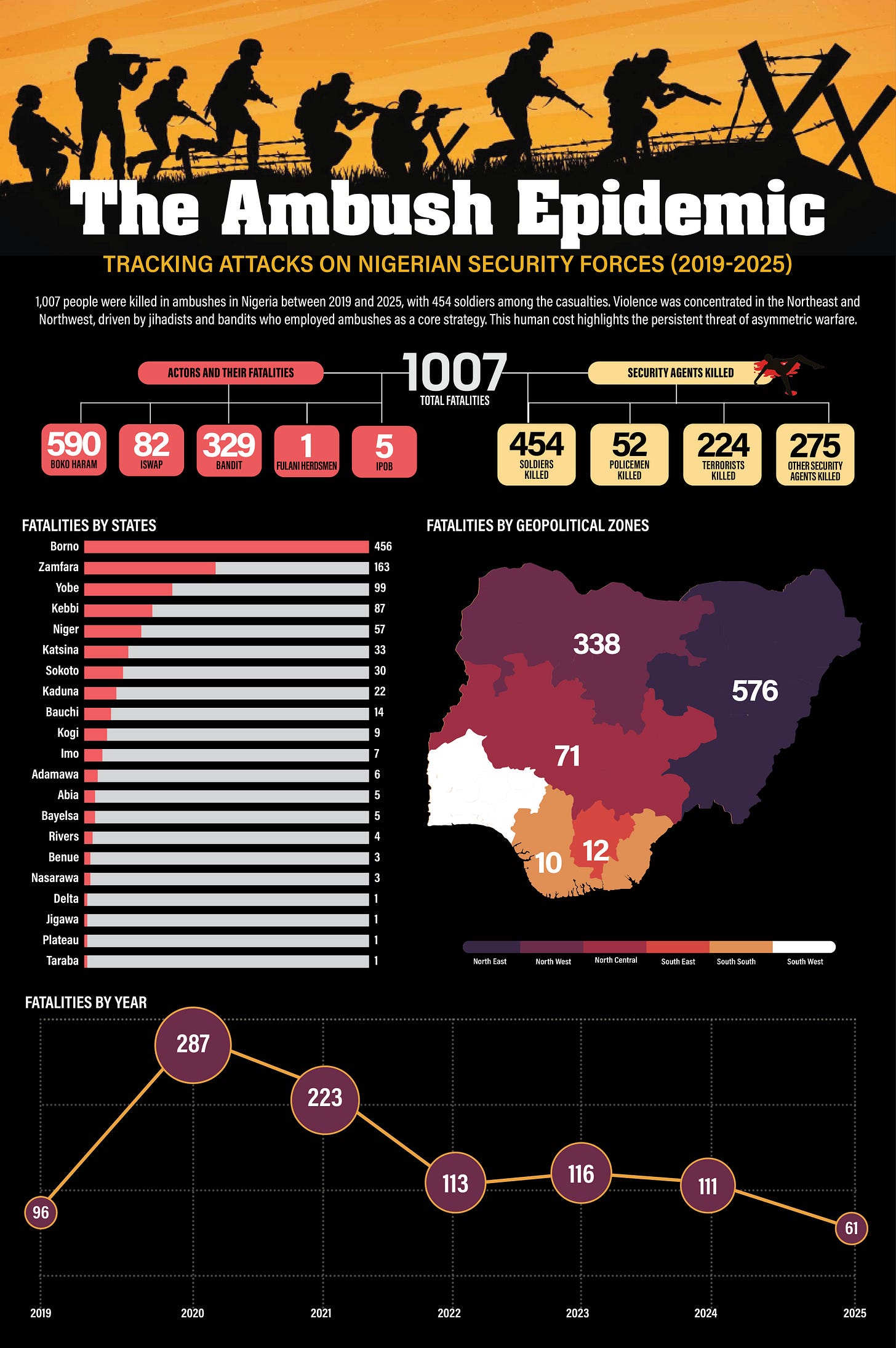

A look at ambushes on Nigerian security forces by insurgent groups between 2019 and 2025.

Nigeria’s frontlines have quietly become kill zones, where soldiers and security personnel are routinely outmanoeuvred by enemies who know the terrain, study their patterns, and exploit their vulnerabilities. The data in this report documents a sustained campaign of ambushes against Nigerian forces between 2019 and 2025 and what it reveals about the country’s wider security crisis.

We have recorded 1,007 fatalities from ambushes in this period, including 454 soldiers, 329 other security personnel such as police, CJTF, NSCDC and vigilantes, and 224 insurgents. Military deaths peaked in 2020 with 174 fatalities, coinciding with intensified operations by the Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP). Fatalities declined after 2021, but renewed ISWAP activity from early 2025 indicates a return to its earlier operational tempo and exposes weaknesses in Nigeria’s counter-terror strategy.

Geographically, the violence is concentrated in the Northeast and Northwest, with Borno accounting for more than 60 percent of recorded ambushes as ISWAP consolidates its presence in the state and the Lake Chad basin. In the Northwest, escalating banditry since 2020 has turned Zamfara into an epicentre of violence and Katsina into a major hotspot, while parts of Niger, Benue and Kogi in the Northcentral, and isolated incidents in Abia, Delta, Imo and Rivers, illustrate a widening theatre of conflict.

The report traces the evolution of tactics. In the Northeast, Boko Haram (JAS) and ISWAP have shifted from crude roadside attacks to complex, multi-stage ambushes featuring improvised explosive devices, assaults on convoys and forward operating bases, fake checkpoints, and the use of explosive-laden commercial drones. In the Northwest and Northcentral, bandit groups increasingly ambush patrols and reinforcements, using diversionary attacks on camps to draw security forces into pre-planned kill zones. Other armed actors, including IPOB-linked elements and ethnic militias, contribute to sporadic attacks on security personnel in the South-East and South-South.

On the state side, the adoption of the “super camp” strategy has provided some protection but also ceded large rural areas to armed groups and turned consolidated bases into high-value targets. Efforts to improve air–ground coordination and to rely more on CJTF and vigilantes have delivered some gains but have come at a high cost in casualties among these auxiliaries. Persistent problems, including inadequate equipment and armoured protection, fragile morale, poor welfare, corruption in defence procurement, intelligence gaps and a weakened Multinational Joint Task Force, continue to blunt operational effectiveness.

The report concludes that Nigeria is locked in a grinding war of attrition. To reduce losses, it calls for better intelligence and reconnaissance, improved mobility and protection for troops, more structured use of local defence groups, serious attention to morale and institutional integrity, and renewed regional cooperation to close cross-border safe havens.