Transactional ties

Donald Trump met African leaders to discuss economic ties and US engagement. Senegal promoted tourism; Liberia was praised. The US is increasing deportations, facing resistance from Nigeria and Ghana.

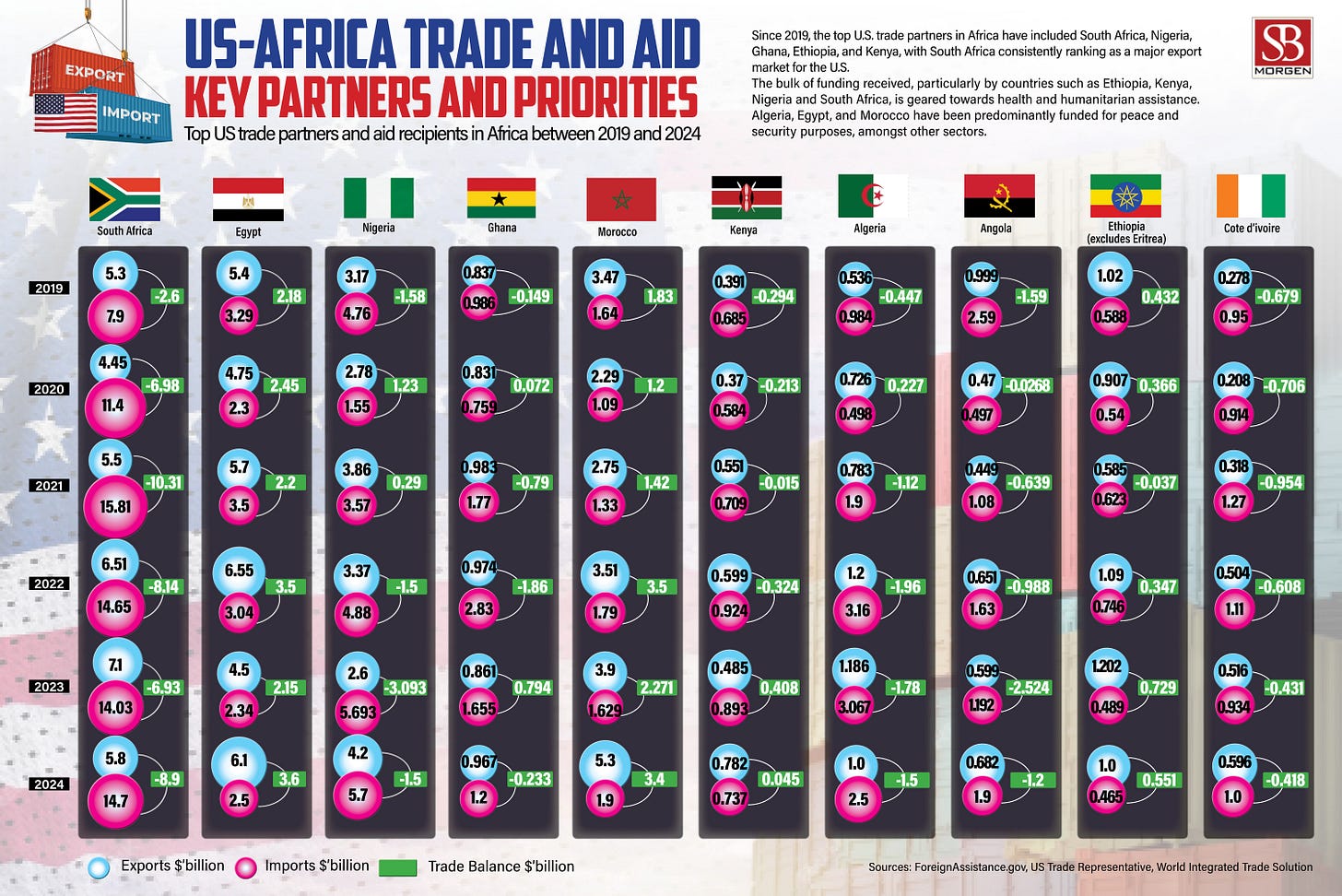

At a White House luncheon with President Donald Trump, leaders from Liberia, Senegal, Gabon, Mauritania, and Guinea-Bissau discussed Africa’s economic potential and praised US engagement, particularly in peace-building. Senegal’s President promoted tourism investment, including a proposed golf course. Trump expressed interest in visiting Africa and lauded Liberia’s President communication skills. The event highlighted a shift in US–Africa relations towards economic cooperation. Simultaneously, the US is intensifying deportation efforts, facing resistance from countries like Nigeria, which refuses mass repatriations. As a result, deportees are redirected to nations such as Niger and Mauritania, prompting US visa restrictions on non-compliant states, including Ghana and Nigeria.

Last week’s meeting has sparked renewed debate about Washington’s intentions on the continent. The meeting, held against a backdrop of increasingly transactional US foreign policy, was ostensibly about boosting trade and countering China’s growing influence. However, it was dominated by blunt demands, particularly controversial deportation proposals that Nigeria’s Foreign Minister Yusuf Tuggar publicly rejected.

The summit highlighted the ongoing evolution of US-Africa relations under the "Strategic Competition" framework, a concept formalised in John Bolton’s 2018 Heritage Foundation speech. Bolton redefined US engagement with Africa through the lens of great-power rivalry, drawing clear parallels with the Cold War’s Containment Doctrine. This posture, which has bipartisan support and is set to continue under a renewed Trump influence, increasingly leans towards coercion rather than collaboration.

While renewing the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA) – a vital trade agreement granting duty-free access to US markets – was on the agenda, this was overshadowed by proposals that threaten to undermine it. Donald Trump’s suggestion of sweeping tariffs, averaging 15% and potentially reaching 50% for countries like Lesotho and Madagascar, could devastate African economies reliant on US trade, undoing decades of progress under AGOA.

Mr Trump's policy platform prioritises access to critical minerals, expanded counterterrorism cooperation, and limiting China’s footprint. Yet, beneath the veneer of "commercial opportunities," the summit also pushed for "safe third-country agreements" – a euphemism for outsourcing the US’s deportation burden. These proposals, which would see African countries receive deportees from nations as diverse as Cuba, Laos, Myanmar, and Venezuela, have been met with quiet resistance. Nigeria’s firm rejection, punctuated by Minister Tuggar’s blunt invocation of Flavor Flav’s "I can’t do nothing for you, man," signals a growing unwillingness to acquiesce. While Eswatini and South Sudan have accepted some deportees and Rwanda remains in negotiations, Nigeria’s refusal may galvanise a broader regional stance against becoming a receptacle for Washington’s immigration dilemmas. Guinea-Bissau’s President Umaro Sissoco Embaló hinted at similar unease, suggesting Trump exercised tactical caution by not making explicit demands in the face of likely resistance.

Discussions around security revealed inconsistencies in US priorities. Trump’s escalation of drone strikes in Somalia—43 in six months, surpassing Biden’s annual tally—reflects a hyper-focused counterterrorism agenda. In stark contrast, the Sahel, where jihadist groups control vast territories, receives markedly less attention. This strategic myopia suggests a policy driven more by optics and tactical gains than by a coherent continental strategy.

Compounding these challenges is the dismantling of USAID’s development apparatus and Mr Trump’s persistent "trade, not aid" rhetoric. By sidelining multilateral frameworks like the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA), the US risks ceding diplomatic and economic ground to China. China's approach, with significant infrastructure investments and soft power efforts—including 90,000 annual student visas for Africans—stands in stark contrast to the US, where student visa denial rates for Africans remain disproportionately high, exceeding 50%, compared to 9% for Europe and 27% for Asia. This disparity fuels the perception that America is uninterested in long-term, mutually beneficial engagement.

Perhaps most damaging is the fallout from US immigration enforcement policies. Over the past decade, thousands of Africans – including asylum seekers, legal residents, and those charged with minor infractions – have been deported with limited coordination. This has strained reintegration systems, undermined diplomatic relations, and disrupted vital remittance flows to economies like Nigeria and Ghana. Deportees often face unemployment, social stigma, or psychological trauma, exacerbating poverty and increasing vulnerability to criminal or extremist networks.

Coercive deportation tactics, backed by visa restrictions and threats of sanctions, further alienate African governments. The Trump administration’s legacy includes documented abuses during deportation, such as shackling, indefinite detention, and denial of legal representation. If left unaddressed, these policies threaten social cohesion, economic stability, and US credibility in the region.

The summit’s exclusion of key players like Ethiopia, Nigeria, and South Africa also raised concerns. This decision appeared to reflect a preference for smaller, more pliable partners, which limited the potential for serious, continent-wide engagement. While Liberia downplayed reported tensions and focused on trade prospects, President Trump’s mockery of President Joseph Boakai’s English left a bitter undertone.

To remain relevant in Africa, the US must recalibrate its approach. Renewing AGOA, aligning security efforts with African priorities, investing in education, and adopting transparent, equitable trade policies are imperative. Without these, the current approach—offering economic carrots alongside deportation sticks—may secure short-term tactical wins but risks long-term strategic isolation.

The summit’s tone, an inversion of President John F. Kennedy’s call to service—"Ask not what your country can do for you..."—reflects an America increasingly asking what Africa can do for it. Such a posture will find limited resonance on a continent seeking partnership, not patronage. Nigeria’s principled rejection of deportation deals may prove to be a watershed moment, signalling a growing assertiveness among African nations to resist unequal arrangements and demand a recalibration of foreign partnerships. The burden now lies with Washington to either evolve its Africa policy toward one rooted in mutual respect and long-term investment—or risk watching its influence recede in the face of better-calibrated alternatives.