US ties deepen with cash and caution

Following Trump's threat of further strikes, Washington delivered military aid to Abuja, which concurrently hired a US lobbying firm for narrative management.

US–Nigeria security cooperation intensified this week as President Donald Trump warned of possible further US strikes if Christians continue to be killed in Nigeria, while Washington delivered new military supplies to Abuja. Mr Trump said additional action could follow the Christmas Day airstrike on Islamic State-linked militants in northwest Nigeria, though Nigerian authorities insist the violence is not religiously targeted and affects both Muslims and Christians. The United States Africa Command confirmed the delivery of military equipment to support Nigeria’s counterterrorism operations, alongside ongoing intelligence sharing and surveillance flights. At the same time, Nigeria’s government hired a US lobbying firm under a $9 million contract to communicate its efforts to protect Christians to US policymakers, highlighting the government's push to manage international scrutiny as security cooperation deepens.

This recent delivery of military equipment differs significantly from the $346 million package approved in August 2025. That earlier tranche covered specific munitions, including 1,002 MK-82 500-pound bombs, 5,000 APKWS II rockets, and related fuzes and control groups from RTX, Lockheed Martin, and BAE Systems, aimed at boosting precision strikes against jihadists. In contrast, the January 2026 supplies, handed over in Abuja by AFRICOM, remain undisclosed in type or value, described only as ‘critical’ equipment to aid ongoing operations following the 25 December 2025 Tomahawk missile strikes on IS-linked sites in Sokoto.

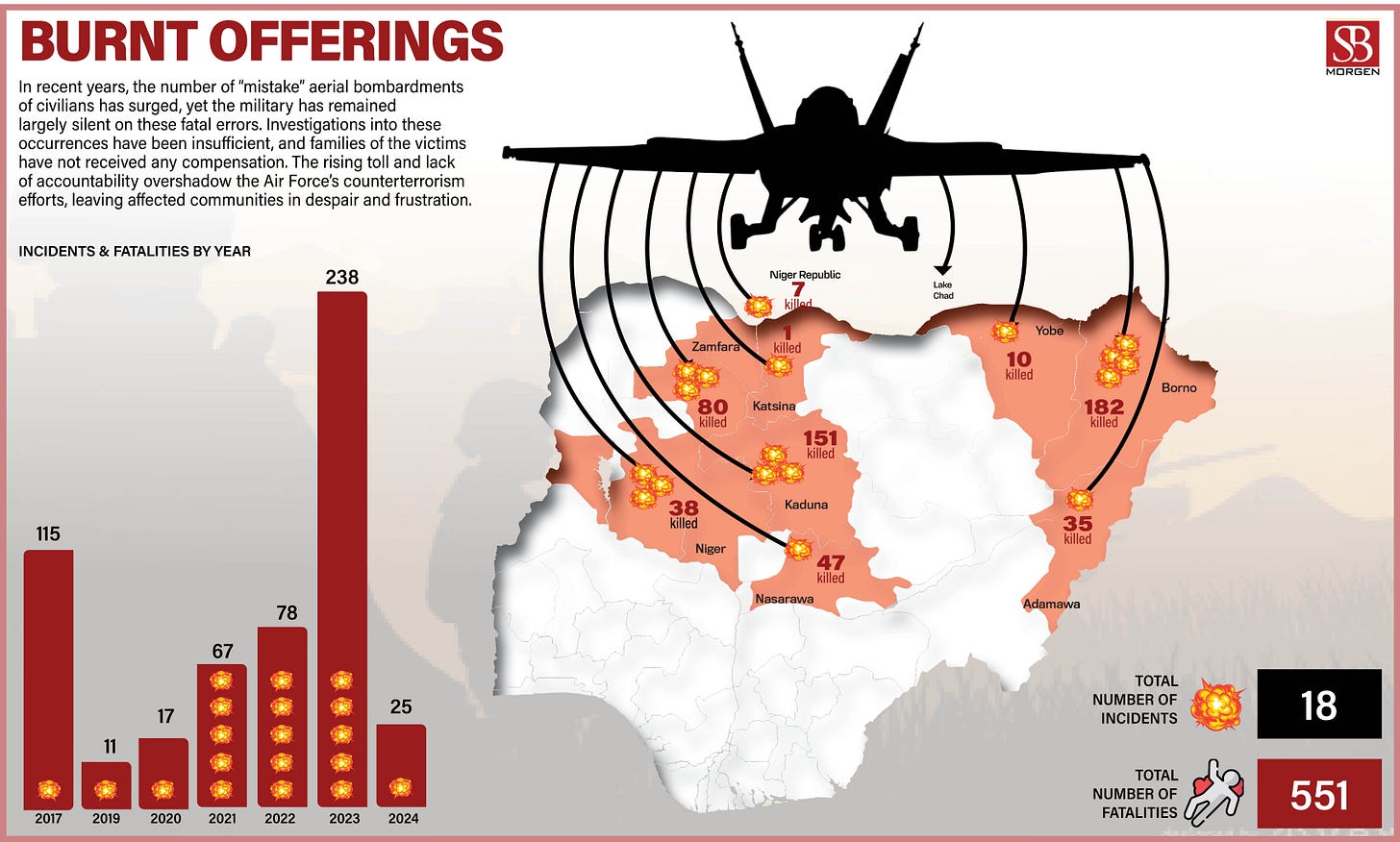

This vagueness invites criticism, particularly as the strikes themselves have become a focal point of conflicting narratives. While the Nigerian government framed the operation as a routine counter-terrorism collaboration, the United States explicitly framed it as a measure to protect religious minorities, a ‘Christmas present’ of sorts. This divergence is not merely rhetorical; it highlights how international concepts like sovereignty are becoming pliable instruments of political messaging. Without detailed transparency, the aid risks propping up ineffective tactics that may kill civilians rather than militants, a concern heightened by the lack of clarity surrounding the damage assessment on the ground.

The supplies connect directly to US reconnaissance missions over northern Nigeria, which reportedly began in November from Ghana. These contractor-operated flights provided targeting data for the Christmas strikes. However, the operational reality reflects a new US foreign policy doctrine articulated in the 2025 National Security Strategy, which prioritises unilateral enforcement over host-nation sovereignty. Under this ‘Trump Corollary’, military action can be timed and framed for domestic US political resonance, overriding the host nation’s narrative. Consequently, Nigeria finds itself in a position where the US may justify intervention by designating local actors as threats to specific groups, such as Christians, effectively bypassing Nigerian command structures.

The risk of further unilateral action is acute. The US could next hit ISWAP strongholds in Borno’s Sambisa Forest or Adamawa, where militants raid Christian villages. This aligns with President Trump’s recent rhetoric; in a New York Times interview published on 8 January, he warned that while he would prefer a ‘one-time strike’, if attacks on Christians continue, ‘it will be a many-time strike’. This threat followed the designation of Nigeria as a Country of Particular Concern in November regarding religious freedom.

In a desperate bid to manage this fallout and reshape the narrative in Washington, the Nigerian government has engaged the DCI Group through a record-breaking $9 million lobbying contract. Signed on 12 December 2025 by Aster Legal in Kaduna State on behalf of National Security Adviser Malam Nuhu Ribadu, the deal includes a $4.5 million retainer paid upfront. The firm is tasked with communicating Nigeria’s actions to protect Christian communities and maintaining US support against West African jihadist groups.

The choice of DCI Group underscores a strategy to leverage Republican connections. The contract involves Justin Peterson, a former representative for Trump, and Roger Stone, a longtime Republican operative and Trump ally. This $750,000-per-month expenditure far exceeds any other current African lobbying contract, signalling the Tinubu administration’s eagerness to end US ostracisation. Additionally, the government has retained Johanna Leblanc of the Adomi Advisory Group to engage with congressional committees on Africa.

However, DCI’s record stinks of controversy. The firm currently represents the military junta in Myanmar for $3 million a year, a regime accused of genocide against the Rohingya ethnic group, as well as Venezuelan political prisoner Juan Pablo Guanipa. The chances of mending ties through such channels may be low, as Republican links might buy only a short reprieve. The structural economic damage is already being felt; the targeting of Nigeria has fundamentally repriced political risk in global commodity markets, introducing an ‘intervention probability’ premium that could dry up long-term investment.

Ultimately, failure looms where violence rages unchecked. Despite the PR cash drain, the reality on the ground—such as the Middle Belt raids where hundreds were killed in 2025—remains grim. The government’s prioritisation of its international image over substantive security reforms exposes a hypocrisy that may further alienate the populace while failing to prevent the very interventions it seeks to avoid.